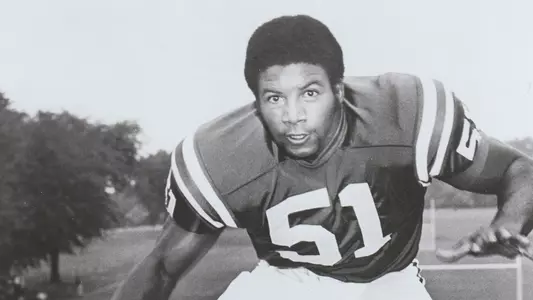

Culture Changer: Bob Grant’s Story Brings People Together, From All Walks of Life

7/27/2021 8:00:00 AM | Football, General

The journey Bob Grant started at Wake Forest has blazed a trail for hundreds of Black student-athletes who have followed his path.

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. -- Bob Grant hadn't just decided where he was playing college football, he had already signed with Michigan State, until an early 1964 conversation with his coach at segregated Georgetown High School, Gideon T. Johnson.

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. -- Bob Grant hadn't just decided where he was playing college football, he had already signed with Michigan State, until an early 1964 conversation with his coach at segregated Georgetown High School, Gideon T. Johnson."You know who this white man is?" Johnson asked Grant, pointing at a picture in the newspaper. "This is Coach Bill Tate. He and the president of the school at Wake Forest are getting ready to integrate college sports here in the South."

With more than 40 college scholarship offers in tow, Grant picked the Spartans, who he was sure were on track to win a national championship — which they did in 1965 and 1966.

"No baby, this is where we're going," Johnson told Grant about Wake Forest. "You are the man for this job."

Grant followed the direction of his coach and mentor, enrolled at Wake Forest in the fall of 1964 and excelled both on and off the field, eventually being drafted in the second round of the 1968 NFL Draft by the Baltimore Colts. He blazed a trail by becoming, along with teammates Butch Henry and Willie Smith, the first Black football players to desegregate a college football team in the South.

"Nobody gave it to me, and believe me it was difficult," Grant said. "It was really hard. There was a lot to endure during those times."

Grant defers a lot of credit to navigating the then-divisive issue of desegregation to Wake Forest President Dr. Harold Tribble, as well as athletic director Gene Hooks and first-year head coach Bill Tate.

"Can you imagine the courage it took for Dr. Tribble, the president of the school at that time, along with Gene Hooks, who was the new athletics director, with Coach Bill Tate, in the South?" he asked. "At that time? In 1964? You never hear those three white men's names mentioned in regards to advances in Civil Rights during that era in the United States. You never even hear their names associated with it, but look at what they did. They made the decision.

"The courage it took for them as white men during that era, it's something that should be mentioned. Nobody else would do it. The people who were making threats at that time had demonstrated that they would follow through."

During the season, Tribble and Grant took weekly walks through Reynolda Gardens.

"Dr. Tribble was more like a father to me when I was there," Grant said. "He supported me. We had a few faculty members who supported us. Every week, we'd walk. He would encourage me and ask me how things were going. We had a very personal relationship. He was one of the most fair people I've ever met in my life, and courageous, as were Tate and Hooks.

"He told me he was getting some of the same (hateful) letters that we were, but as long as we were willing to play they would be there for us."

Tribble would ask Grant about his social life at Wake Forest and if he was being treated fairly across the board by his professors.

"The answer was no, but that was okay," Grant said. "That was all just part of the way things were back then."

On the field, Grant was a physical player who imposed his will on opposing offensive lines. Jody Puckett, who served as student athletic trainer during Grant's time at Wake Forest, remembers coming to Demon Deacon football games with his high school football coach Joe White.

"They have a defensive lineman named Robert Grant," White told Puckett. "I focused on him and watched him beat the hell out of the guy across the line of scrimmage. He's that good."

Tight end Rick Decker, who also was a 1964 enrollee, was glad Grant was on his side.

"Bob was terrifying on the field," he said. "He was 6-foot-3, and 225 pounds of all muscle. He had a body like a bodybuilder, with 20-inch arms. He was a hitter."

As an offensive lineman, Bob Oplinger had to square off regularly against Grant, especially when he earned the ire of Coach Tate.

"When Coach Tate knew I needed more work or a harder day at practice, he would put Bob Grant over me," Oplinger said. "Bob would just knock the hell out of me. We were about the same size, but he was a lot faster and stronger. We were told he had a black belt in Karate, so we didn't want to mess with him."

Quick and decisive on the field, Grant earned the reputation as one of the most fierce defenders in the ACC in that era.

"Bob was an immediate first-team guy," offensive lineman Runo Anderson said. "When the guys got in the games, there was a different camaraderie that comes with the first-team. He took his job seriously. We knew he would get a chance in the NFL.

"Bob was always willing to help me with technique on the offensive line, sharing what he learned from squaring off against me. He did his thing, but was quick to give me advice."

Working alongside him on the defensive line, Tom Stuetzer gained a tremendous amount of respect for Grant.

"He was a man among boys," he said. "He always had the most potential on the team. He was fast and agile, but also had a basic goodness about him that transcended a lot of things. He had a good heart."

Bill Overton transferred to Wake Forest in 1966. During their junior season, Overton and Grant were about to meet on a stairway, but for whatever reason Grant hadn't seen his teammate.

"I jumped over part of the railing to surprise him," Overton said with a laugh. "Bob, being a black belt and defensive end, throws his arm and elbow up to block me. He hit me right in my jaw. That's probably one of the hardest hits I've ever taken in my life, but I didn't let him know he'd hurt me."

Overton figures that Grant likely felt if he could withstand that shot, then he's alright as a teammate on the field, and that trust was important with them playing on opposite ends of the defensive line.

"I'll meet you at the quarterback," he often said to Grant, who he credited with being strong, agile and quick with an outstanding vertical leap.

Though Grant's grandmother was initially wary of him playing at Wake Forest, his grandfather, Kai "Sam" Grant, counseled him to just be great at whatever he does, and he'd eventually earn acceptance. His grandfather, who was born in Haiti in 1894, was a friend of "Galveston Giant" Jack Johnson, the first Black world heavyweight boxing champion, and never missed a title bout fought on American soil.

"People used to pay $100 to see champion Jack fight," Grant's grandfather told him. "With Joe Louis, everybody fell in love with him and wanted to see him whip Max Schmeling. Now with this new guy from Kentucky, (Cassius) Clay, anyone would pay a lot of money to see him fight.

"If you go up there (Wake Forest), and you turn in a championship performance in everything you do — games, practice, the way you carry yourself and in the classroom — before you leave there, I believe it'll be your fans the same way people were fans of champion Jack."

Those words rang true as Grant slowly won over fans not only in Winston-Salem, but across the conference.

"That became obvious by the time I was a junior," he said. "It was always in my mind to give a championship performance in everything you're doing. It starts to change on campus for us then. And even on the road, it starts to change quite a bit.

"I beat the hell out of everybody all over the South who we played against, which is why I ended up being the No. 50 draft pick. I became the first Black player out of the South to play in the NFL."

While the bonds among teammates were strong, that didn't carry over campus-wide — at least not initially for Grant and Henry.

"Our social life the first couple years was just us," Grant said. "We had our own little community. There were 26 other people outside the athletes on the campus who weren't afraid to be seen talking to us.

"We knew who they were. We used to chuckle about it. Even trying to get eye contact was a challenge. There was peer pressure. They didn't want to be seen talking to us or at a table with us. That was okay. We understood and knew what the times were. It wasn't about anybody being mean or anything like that. But there were 26 souls among the student body that didn't care. We'd talk, go to the cafeteria and enjoy grilled peanut butter and jelly sandwiches."

Each year's recruiting class brought a few more Black athletes onto campus, and bonds were shared across the various athletic programs.

"We didn't have a choice," Grant said. "I won't say it was lonely. There were the three of us the first year. Then the next year, Wake Forest brought Howard Stanback and Jimmy Johnson in the football program."

The second year brought Tom Gavin (football) and Norwood Toddmann (men's basketball) to Wake Forest's campus, followed by two more basketball standouts, Charlie Davis and Gil McGregor.

"Our community expanded a little bit year-by-year," Grant continued. "So Butch and I became the older brothers for those guys. Things loosened up a bit on campus each year."

Along the way, the network of Black athletes became known as The Boys.

"It was an interesting time," Overton said. "Whoever recruited them did a great job. They both were just nice guys, and I say that so easily. I take my hat off to the recruiters. There were no knuckleheads. I'd be shocked if Butch or Bob ever had an argument. The three of us never had an argument."

Grant had a four-year NFL career, including two trips to the Super Bowl with the Baltimore Colts. The Colts beat the Dallas Cowboys 16-13 in Super Bowl V, earning Grant a Super Bowl Championship ring. Grant later served as president of North Shore Traders Inc., an investment firm with offices in Southern California, Nevada and Hawaii. He currently serves as Chairman of Board at the Retired NFL Players Congress. Grant was inducted in the Wake Forest Athletics Hall of Fame in 2011.

The journey that he started at Wake Forest has blazed a trail for hundreds of Black student-athletes who have followed his path.

"My life has been a great life," Grant said. "My every dream has come true, and I'm still working to make a contribution. I've enjoyed my entire life. Ego has not been a big part of who I was in the past, and it's not a big part of who I am now. I've always been a team player. That's the way I was raised."

Football Media Availability (9/18/25)

Thursday, September 18

Matt Barrie SportsCenter at Wake Forest with Demond Claiborne

Wednesday, September 10

Matt Barrie SportsCenter on Wake Forest Campus (Arnold Palmer Complex)

Wednesday, September 10

Football Media Availability (9/9/25)

Wednesday, September 10