Culture Creator: Kenneth “Butch” Henry Set Standard On & Off The Field

7/28/2021 8:00:00 AM | Football, General

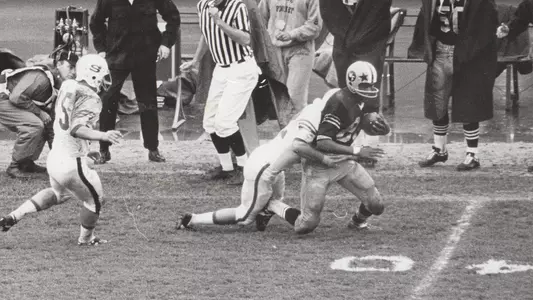

Trailblazer Kenneth “Butch” Henry was the first Black athlete to sign with Wake Forest.

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. -- Kenneth "Butch" Henry changed lives by playing college football at Wake Forest University.

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. -- Kenneth "Butch" Henry changed lives by playing college football at Wake Forest University. One example is Steve Bowden, who saw a Henry highlight-reel play while at an all-conference event as a high school sophomore.

"The speaker at the event was an assistant coach from NC State," Bowden said. "He gave his talk then showed a film. It was a highlight film for NC State, showing action against all of their opponents. But when it got to Wake Forest, Butch Henry makes a play. I don't know why they put this in the film.

"The coach even said that the football player from Wake Forest is Butch Henry, and that he's going to be one of the top receivers in the Atlantic Coast Conference, and then kept going."

That resonated with Bowden for years, and when it came time to make his own college decision, he proudly chose to be a Demon Deacon.

"The only black face in that entire video was a Wake Forest player, and I don't know if they showed anybody but Butch," he said. "But they showed Butch.

"They have Black athletes at Wake Forest. That stuck with me then."

Henry blazed trails by being the first Black athlete to sign with Wake Forest and, along with teammates Bob Grant and Willie Smith, as the first three Black football players to desegregate a college football team in the South.

With the authorization from Wake Forest President, Dr. Harold Tribble, first-year football coach Bill Tate sought to integrate the program shortly after his hire in early 1964. His first signee was Henry, from Dudley High School in Greensboro.

"Henry lived in a decent section of town in Greensboro and grew up in a comfortable environment," Bowden said. "At the time, Dudley athletes were going to the Big Ten. Butch would have been a Big Ten guy, but Wake Forest recruited him, and he decided he wanted to do it."

When he spoke with reporters after signing with the Deacs, Henry acknowledged that being the first Black athlete on campus in Winston-Salem could potentially present a few challenges.

"Times are changing, and everything should be all right at a school like Wake Forest," he reportedly said at the time.

NCAA rules at the time were that no freshmen compete with the varsity team, and by the time Henry and Grant were sophomores, they were joined in the ACC by just two Maryland players as the only four Black players in the conference.

"During that time, nobody else was recruiting Black athletes in the ACC," Bowden said. "So Wake Forest could get the very best Black athletes available. He and (Bob) Grant were just incredible athletes. It's hard to put into words just how good they were."

A converted quarterback, Henry picked up the receiver position quickly, with great physical tools coupled with a sharp intellect and hard-driving work ethic.

"He looked like a modern-day wide receiver," then student athletic trainer Jody Puckett said. "Butch was about 6-foot-4, long and lean. He could really run. His first varsity game, he caught eight passes, which tied a record back then."

Henry quickly became the top target for Wake Forest quarterbacks Jon Wilson and Kenny Hauswald in his first year of eligibility as a sophomore in 1965, catching 30 passes for 367 yards.

"Butch and I were both split ends, and we were on opposite sides," Tom Stuetzer, a fellow wide receiver, said. "I knew there was a difference between us because he was fast and I was relatively slow. He was smooth and I wasn't.

"We had to do sprints all the time. Trying to keep up with Butch, you just couldn't do it. He would glide and I would be struggling all the way down. I'd finish second or third, but could never beat him. He would just glide. That's why we called him Smooth."

Joining him in the receiver room with position coach Beattie Feathers was tight end Rick Decker.

"Butch was always a leader and someone to admire," Decker said. "He was a great football player. He could play almost any position on the field, except offensive and defensive line. But he was a great player and a great person. I really got to love him as a teammate and a brother."

By the fall of 1964, Grant, a defensive lineman, joined Henry as they started their four-year groundbreaking journey at Wake Forest together.

"Butch was a phenomenal athlete, which anyone who played with him will tell you," Grant said. "He was not just the best all-around athlete — Butch could have played varsity basketball. He was probably the best all-around athlete in the entire South."

By the time both Decker and Henry were seniors the Deacons had added McCook Junior College (Nebraska) transfer Freddie Summers, a talented signal caller who became the first Black quarterback in the ACC. He was able to spread the ball around to his receivers, and Henry was his go-to deep threat.

"He was tall with a great reach," Wake Forest offensive lineman Runo Anderson said. "He could get open and outsized defensive backs, who weren't usually taller than six-feet. He was fast and agile. He was able to get up in the air and bring down catches other people simply could not."

Beating Summers to Wake Forest from McCook by a season, while also playing a big hand in getting the quarterback into Winston-Salem, was defensive lineman Bill Overton, who built a strong relationship with Henry.

"I immediately was connected with Butch and Bob, because we were in the same class, and they were roommates," Overton said. "It was an interesting time at Wake Forest and around the country. We became like peas in a pod, except for on weekends, because three's a crowd."

Henry was the one in the group who actually had a vehicle at his disposal, and he would travel back home to Greensboro on occasion, according to Overton.

"Butch was a ladies man, but both were incredibly likeable," he said. "Being local, Butch was more of a legend from a social standpoint. I was the odd man out, often. But we also didn't have a whole lot of time, other than football activities and then studying. You couldn't fool around. Wake Forest was not easy."

One Sunday morning, Henry carted both Overton and running back Jimmy "The Jet" Johnson with him to Greensboro for church and a meal at his house.

"That was my first exposure to banana pudding," Overton recalled. "I never forgot that. Oh man."

Overton said he grew up attending a conservative protestant church in the Boston area, where the audience was hushed and quiet. The church Henry took them to in Greensboro was not quite the same.

"We sat in the balcony of all-black baptist church, with a full band and the pastor in a cape," Overton said. "He proceeds to glide across the stage like Michael Jackson moonwalking. I lost my mind. Then they proceeded to bring the house down. It was the most inspirational, entertaining church service I'd ever gone to."

When Overton got back to campus, he immediately called his mother.

"You would not believe what I just experienced," he told her. "I was a babbling idiot. I'd never seen anything like that in my life."

"It was like it was a show. I say this with the utmost respect. I'll never forget that."

During the summer entering their senior seasons, a Henry family friend, Amos, hired him and Overton for a job in Newport, Rhode Island.

"He would clean oil tanks that were built underground, so in case of war all the tanks weren't above ground," Overton said. "In Newport, they were underground. The fumes in the tank, you had to be careful, even though the tank was empty. We had to put on gas masks and a whole rig like we were going to the moon or something. Then we'd climb down there. The only lights we had, we brought with us. Then we'd have to scrape the walls of those tanks. They were huge. That was one of the hardest jobs I ever did in my life.

"Then we'd spend time at my mother's house. We did that for a month, so we were able to get real close."

By the time Bowden started going through the recruiting process, he had been following Wake Forest and Henry — then got to see him interact with his teammates while on an official visit.

"The guys were just so comfortable," Bowden said. "Though folks would say they were isolated, they were a family and had great camaraderie. I was quiet and to myself on the visit, just taking everything in. And these guys were just so comfortable, having fun with each other. That struck me, how close they seemed to be.

"When you were being recruited, they let you know that you were going to be part of that family. You could tell that there was something special going on. It was a special, special time. It all traces back to Grant and Butch. They came in first and created that atmosphere. They recruited more black athletes and the culture was being put together."

Henry and Grant established a strong culture for Black football players at Wake Forest, that started with being good teammates, excellent students and phenomenal football players.

"They also had a culture around the Black athletes," Bowden said. "Society was as it was, not as we wished it was. I don't want to give an illusion that they were in some angelic environment where everything was fine. They weren't. The real world in that era, they were facing.

"They were good friends with a lot of people up and down the line, but at the same time there were a lot of people who didn't want them there. But in that environment, where there clearly would be some hostility, they had a tightness between them and as more Black athletes were brought in they made sure there was a bond. That created a camaraderie and a closeness in a group that is hard to put into words about how special it was."

Life on campus was still a bit frosty and the team as a whole faced some hostile environments in the South because of the choice to integrate, but Henry and Grant found solace with each other, with their teammates and then in social circles with the growing number of Black athletes who were recruited in subsequent classes.

"You weren't upset about having that cocoon of friendship that you didn't want to move out of, because that was the world in which we lived," Bowden said. "But in that reality, we loved it, because we loved each other. It was a special, special time. That was a marvelous time when you were a young man.

"They set the stage and set the tone that Black athletes could come and feel comfortable. They did it."

Bowden became a Demon Deacon in 1968, and was on the freshmen team during Henry's senior campaign, something that likely never happens if Henry hadn't broken through in 1964 and been on that highlight tape Bowden watched as a high school sophomore all-conference player.

"I was an easy mark for Wake Forest," Bowden said. "They had something to offer, don't get me wrong, but I already had an affection for them from my sophomore year in high school."

Henry's success at Wake Forest opened the doors blazed the trail not only for Bowden, but for hundreds of Black student-athletes who followed in his footsteps.

"Without Butch Henry being on that screen and getting Wake Forest in my head, I probably wouldn't have been there," Bowden said. "I visited North Carolina six times, but I was already partial to Wake. I had a weak spot in my heart for Wake Forest, and that starts with Butch."

Wake Forest vs Mississippi State | Duke's Mayo Bowl Cinematic Recap

Friday, January 09

Steve Forbes - Postgame Presser vs. Miami

Thursday, January 08

Steve Forbes - Postgame Presser vs. Virginia Tech

Saturday, January 03

Head Coach Jake Dickert Duke's Mayo Bowl Postgame Press Conference (Jan. 2, 2026)

Saturday, January 03

.jpg&height=340&type=webp)